Imported Bronze Coins in Roman Achaea

A rhetorical exaggeration has been for a long time one of the main sources for the analysis of the Roman economy in the province of Achaea. Seneca in the first century AD posed the question “Do you not see how, in Achaea, the foundations of the most famous cities have already crumbled to nothing, so that no trace is left to show that they had even existed?” (Seneca, Letters, 91.9-11 Transl. by in Loeb) Although the author had earthquakes in mind rather than economic decline, these words influenced modern academics in their interpretations of the Achaean economy under Roman domination. Similarly, when Strabo talked about Arcadia he claimed that “on account of the complete devastation of the country it would be inappropriate to speak at length about these tribes; for the cities, which in earlier times had become famous, were wiped out by the continuous wars, and the tillers of the soil have been disappearing even since the times when most of the cities were united into what was called the “Great City.” But now the Great City itself has suffered the fate described by the comic poet: “”The Great City is a great desert.” And yet, Strabo adds that Arcadians were well-known for breeding excellent horses (Strabo, 8.8.1. Transl. by H.L. Jones in http://www.perseus.tufts.edu)

Historians’ misconceptions were partly moderated when Suzan Alcock published her book in 1995 Graecia Capta: The Landscapes of Roman Greece, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. She used extensive archaeological evidence from the Greek mainland in order to reconstruct the economy of the region. She talks about changes in the countryside that show the existence of large landholdings and benefited the wealthier elements of Achaean society. She assumes that preferences for nucleated residences in the urban centers, which were the result of economic pressures and greater social polarities. She claims that the peripheral position of Greece within the empire is indicated by the distribution and number of cities across its lands. The redistribution of land combined with a preference to reside within larger communities could, according to Alcock, confirm a wider demographic decline. She also confirms that the province of Achaea was not necessarily in permanent decline as moralists would be inclined to say. Although its position in the Roman empire was not as illustrious as it used to be during the Hellenistic period, we are hard pressed to see this province as the backwater of the Roman empire. And yet, it is widely accepted that the land did not flourish as it happened in Asia Minor, while only a few urban centers could have been considered prosperous.

Numismatic finds from excavations confirm the prosperity of at least three major urban centers (Athens, Corinth and Patras) and two ports on either side of Corinth (Kenchreai and Argos/Lechaion) during the second and third centuries AD. This prosperity could be measured through the regular importation of small change from distant areas. Bronze coins are an excellent indicator for the monetisation of a region, since they are used in daily transactions. Furthermore, they are predominately found in the course of excavations, because they are of small value and their owners may not care excessively about their recovery. Usually they travel within a radius of around 200 km but they may move even further in exceptional cases. The patterns of their movements could reveal whether the region we are interested in exhibited local, regional, or inter-regional patterns of trade. In the case of Greek cities we will focus on the presence of imported coins from distant areas in the archaeological record in order to prove inter-regional movements of people that contributed to the prosperity of the urban centers and their territories.

Athens

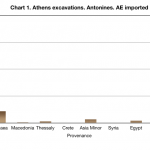

Athens in the first instance had lost her empire and prestige already by the fourth century BC. During the second and third centuries AD she was part of the powerful Roman empire and was already adjusted to provincial dictates. Coins coming from the excavations of the agora present us with the following picture. During the Antonine dynasty we notice that the majority of bronze coins found in Athens have been minted in the city itself (1603 out of 1881). If you look at the numbers of coins in the following chart that come from different regions, you will notice that the mint of Rome (221 coins) outstrips even the neighbouring cities of the province of Achaea (33 coins). Another area that is noticeable is that of Asia Minor (10 coins). Otherwise, we encounter bronze issues from the entire eastern Mediterranean, including Egypt that kept a closed currency system. Chart 1.

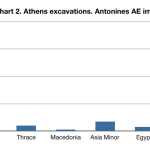

The numismatic picture of Athens remains similar throughout the Severan period. Athenian coins remain widely in circulation but they are still complemented mostly by coins from the mint of Rome (78 coins) and Achaea (33 coins). However, in this case we notice a shift towards using more coins from the provinces, including distant areas such as Asia Minor (7 coins) and Egypt (3 coins), rather than the mint of Rome in terms of absolute percentages Chart 2.

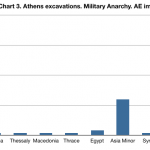

By the Military Anarchy period Athenian coins continued to be used in abundance in the local markets (1056 out of 1127 coins) but almost no coins from the province of Achaea. While Achaean coins disappear from the markets, coins from Rome (48 coins) and Asia Minor (15 coins) continue to be imported alongside a handful of coins from northern Balkans, Egypt and Syria. Chart 3.

The Athenian empire slowly but steadily was eroded during and after the Peloponnesian War; alongside the political erosion, its hold on interregional trade became weaker. During the Hellenistic period the Aegean Sea was controlled by the Macedonians, the Seleucids and the Ptolemies, while Athens was just a shadow of its previous economic power. From 166 BC onwards Delos, a free port in the middle of the Aegean, became a center of commerce and business under the auspices of the Romans. After the establishment of the Roman empire across the Mediterranean other commercial centers in southern Greece attracted interregional trade. Among them were Nikopolis, Patras, Corinth and, of course, Athens (Migeotte 2009: 133). Athens had the advantage of three ports in each vicinity, one of which, Peiraieus, was well known for its geographical advantages to sea trading. On the whole, Athens may have lost its empire but it continued being a hub of commercial activities throughout the Principate.

The following chart gives us an idea of foreign trade in Athens and place of origins of the merchants that were active in the area. These names were included in sepulchral inscriptions that have been found in and near the city of Athens and its port the Peiraieus. The names have been gathered together in a comprehensive table by John Day (1973: 214). The figures for regions include the figures for cities in those regions, except from Bithynia, Pontus and Propontis that is not included in Asia Minor. Here we notice that during the Roman Principate more merchants from Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt arrived to the city in order to trade their commodities. They traded alongside merchants from northern Greece, Boiotia, the Peloponnese and Italy.These results are reflected also in the patterns of the coins that include issues of these eastern areas. Day assumes that the foreign merchants sold their products to those who adorned the city, or bought objects of art from Athenian artists, or sold their wares in other parts of Greece (Day 1974: 218.). It is more likely, though, that they played the role of middlemen in the lucrative interregional transit trade that took place in Athens. After all, the existence of a large number of coins from the mint of Rome among the excavation finds could indicate commercial activities towards the direction of Italy.

|

Foreigners in Athens |

|||

|

Table 3 |

ORIGIN |

403 BC to AUGUSTUS |

IMPERIAL |

|

Northern Greece |

115 |

20 |

|

|

Boiotia |

61 |

12 |

|

|

Thebes |

33 |

2 |

|

|

Peloponnese |

50 |

19 |

|

|

Corinth |

18 |

6 |

|

|

Sikyon |

13 |

2 |

|

|

Karystos in Euboia |

6 |

13 |

|

|

Bithynia, Pontus, Propontis |

183 |

128 |

|

|

Heraclea Pontica |

96 |

90 |

|

|

Sinope |

24 |

11 |

|

|

Asia Minor |

125 |

469 |

|

|

Miletos |

48 |

342 |

|

|

Ephesos |

15 |

2 |

|

|

Ankyra |

8 |

30 |

|

|

Syria |

65+ |

133 |

|

|

Antioch |

39 |

118 |

|

|

Alexandria |

7 |

23 |

|

|

Italy |

14 |

15 |

Apart from interregional trade and passing boats, we notice that Athens was also an important center of knowledge. During the first century AD the city’s schools attracted young visitors from the entire Roman empire. Our information comes from the ephebic lists that mention a large number of foreigners who were officially registered. In addition, it looks like most of these students came from affluent Roman families from either Rome or the province; consequently, they had the financial capacity and the monetary resources to pursuit a comfortable lifestyle. The influx of foreigners in Athens continued well into the third century, when the economic crisis struck all of the Roman provinces (Day 1973:182 and 253-4). These students would have boosted local businesses, modern parallels of which we may find in modern university towns. The economic lives of the Athenians were further enhanced upon the arrival of the emperor Hadrian in the city, who became its most illustrious benefactor. Hadrian funded an ambitious building program that included the Temple of Olympian Zeus, the inauguration of the Panhellenion, the Pantheon, the construction of an aqueduct; all of these transformed the urban center, while they required the spending of large sums of money (Shear 1981: 19).

In the excavations of Athens we notice the highest concentration of coins that come from distant areas around the Mediterranean. Although most of the bronzes were issued in the mint of Athens, the coins from the mint of Rome form the second largest sum of coins in the area. Even the coins from the neighbouring Achaean mints are underrepresented by comparison. The Roman ‘official’ coins finally become the predominant means of daily transactions in Athens by the middle of the third century AD, when most civic mints closed down. In addition to those, we find coins from Asia Minor, northern Greece, Syria and Egypt in small but telling numbers.

Corinth

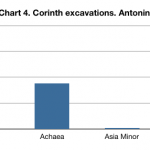

Our next case study is the colony of Corinth, another important harbour in north-eastern Peloponnese. Unlike Athens the percentage of coins minted in the locality (Corinth) is far smaller than the percentage of Athenian coins found in Athens. Specifically, only 120 coins were minted in Corinth out of a total of 246. A substantial amount of the rest come from Rome (58 coins), from Achaea (66 coins) and only 2 from Asia Minor. Chart 4.

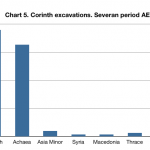

In the Severan period the patterns are significantly different, since we find almost as many Corinthian coins as the ones that come from other Peloponnesian mints. At the same time we finds a non-negligible number of coins from the mint of Rome and a handful of bronzes from areas north of Achaea as well as Asia Minor. Chart 5.

As in the case of Athens, coins no longer came from Peloponnesian mints. In fact, importation of bronzes decreased substantially. The mint of Rome remains the main representative in the archaeological record. I should note here that no coins found in Corinth have been minted in the mint of neighbouring Athens, although Corinth coins have been found in Athens. The reasons cannot be economic ones, since bronzes normally circulated freely between neighbouring cities. Instead, we should explore ideological reasons. Another case study that may be of use in this case is the city of Laodicea and its neighbour Antioch in the province of Syria. Chart 6.

It is also worth mentioning the few coins that have been unearthed in the two Corinthian porrts in north-eastern Peloponnese: a) Kenchreai, b) Argos and Lechaio. In the first case of Kenchreai, the majority of coins come from Achaea and Rome, with only 1 coin from Egypt (Antonines) and 1 from Macedonia (Military Anarchy). We should bear in mind that only 36 coins have been found in this chronological context.

|

Table 1 |

||

|

Kenchreai excavations |

||

|

Antonines |

PROVENANCE |

AE |

|

Achaea |

12 |

|

|

Rome |

4 |

|

|

Egypt |

1 |

|

|

Severans |

Achaea |

8 |

|

Rome |

2 |

|

|

Anarchy |

Achaea |

1 |

|

Macedonia |

1 |

|

|

Rome |

7 |

On the other hand, in Argos and Lechaio, even though only 26 coins have been found, two came from Ionia, 4 from Rome, while the rest were minted in Achaea (predominately in Argos). So, also in these peripheral cases there is a strong representation of Achaean mints, a substantial number of coins coming from Rome and a handful of coins from Egypt and Asia Minor. The mint of Athens appears nowhere.

|

Table 2 |

||

|

Argos/ Lechaio excavations |

||

|

Antonines |

PROVENANCE |

AE |

|

Achaea |

10 |

|

|

Rome |

3 |

|

|

Ionia |

1 |

|

|

Severans |

Achaea |

8 |

|

Ionia |

1 |

|

|

Anarchy |

Achaea |

3 |

|

Rome |

1 |

The commercial significance of Corinth was noted in antiquity; especially in the work of Strabo who mentions that Corinth is called wealthy because of its commerce and because of the location of its two harbours on each side of the Isthmus. The city of Corinth has always been dominated by the operation of its ports, one on the Aegean side and the other on the Corinthian Gulf. One of the harbours led to Italy and the other to Asia. Strabo continues his analysis emphasizing on the favourable position of the colony in terms of seasonal winds and distances. He concludes that traders preferred landing in this area and, as a consequence, the annual taxes coming from trading activities were substantial (Strabo ???). It is true that many boats that traveled from Asia to Italy and vice versa unloaded their cargo in one port, transferred it through diolkos, and uploaded it in the other port with the intention to save a 6 day journey around the Peloponnese. Engels acknowledges the implications of Strabo’s views as well as the geographical position of the city and claims that Corinth’s wealth came from the provision of services to these travelers. These services could be divided in two groups: a) primary services that attracted travelers and merchants, and b) secondary services which these individuals needed after they arrived in the city. On the whole, these visitors used the city as a stopover point between east and west and spend their money in the local markets. Commerce dominated the local economy to the point that the inland agricultural activities were neglected (Engels 1990: 50-52).

Probably also because of the geographical position of the city, the Romans turned Corinth into a colony and rebuilt it to Roman standards, especially after the earthquake of 77 AD. By that time the porous buildings of Corinth were replaced by buildings of imported marble and other non-local materials (Engels 1990: 61-62). In the first and second centuries AD the city profited from its geographical position between east and west. Its citizens not only traded commodities, thus participating in the flourishing inter-regional trade of the eastern Mediterranean, but they also benefitted from their banking activities. Plutarch mentions that Corinth was one of the main centers for money-changing (Plutarch, Moralia, 831). This comment makes perfect sense, if we take into consideration the fact that trade is greatly facilitated by the use of money; in turn it allows for the banking profession to flourish. These activities were complemented with the benefits arising from Corinth’s status as an assize center, according to Dio Chrysostom (Dio Chrysostom, Or., 35. 15-6). Large number of people carrying coins may also have been attracted by the presence of the provincial governor in the city. On the whole, since the city was a center for the collection of taxes combined with lucrative banking businesses and interregional trade opportunities, the occasions for profit probably multiplied during the Roman empire (Hoskins Walbank 2002: 259), as a result of the pax romana and the overarching Roman administration.

Studies of the pottery coming from Corinth confirm evidence from ancient sources, whether these are geographers, historians or others. Specifically, a study of amphoras found in the area indicate that 85 per cent of them were imported, while fewer than 15 per cent were local (Warner Slane 2003: 327). This percentage is in contrast with some African sites, also known for their participation in interregional trade. For example, at Sabrathe local Tripolitanian and/ or Tunisian amphoras account for more than 40 per cent of the total and at Carthage they form more than 50 per cent (Fulford 1989: 181-4). Amphoras in archaeology are always connected with interregional trade. On the other hand, we notice that in Corinthian excavations the importation of fineware form 30-35 percent of the total (though during the Augustan period they reach 66 per cent). Such strong local production is also dominant in the case of lamps that form a low of 62 per cent during he reign of Trajan, while they peak to a 97 per cent in the third quarter of the third century AD (Warner Slane 2003: 330-331). All of this evidence is indicative of Corinth’s central position in interregional trade in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Furthermore, the mosaic of imported bronze coins indicates the significant role of the colony in interregional trade. As it is expected in a provincial city, most of the coins found in arcaheological excavations have been minted in Corinth or in neighbouring cities. The Achaean mints that are more strongly represented are those of Patra and Corinth; thus, indicating continuous movements of people between these two regions and most likely beyond them, towards Italy in the west and Asia Minor in the East. Accordingly, we find a very large number of coins from Rome and some coins from Asia Minor. This pattern changes during the Military Anarchy period, not necessarily because these movements stopped but because the monetary system itself changed. With the gradual closing down of civic mints, we see during that time the increasing production of bronzes in the mint of Rome and other centrally placed ‘official’ mints.

Patrai

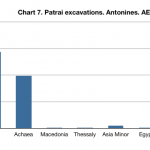

In north-western Peloponnese another Roman colony became an important harbour. In the following chart 7 we notice that during the Antonine period most of the coins that circulated in the harbour were minted in Patrai (108 coins) itself. An equally large number (74) came from Achaean mints, of which Corinth seemed to be the most prolific (60 coins). Also here we find no coins coming from Athens. Almost a quarter of the coins found in excavations were minted in the mint of Rome (64), a fact that could be interpreted because of the geographical position of Patrai. Chart 7.

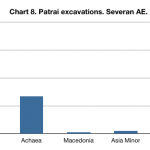

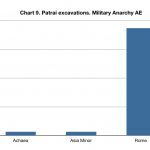

In the following chart we notice similar patterns. Most of the coins found in Patrai excavations came from Patrai (72), Achaean mints (27) and Rome (23). However, the eastern provinces of Asia Minor are also represented as in the previous period. Chart 8.

Finally, during the period of Military Anarchy the number of provincial coins was almost extinguished. Most of them come from the mint of Rome. Chart 9

Patrai was the counterpart of Corinth in the north-western part of the Peloponnese. It similarly facilitated the east-west interregional commerce; so, it was probably the first port of call for the boats coming from southern Italy. This is probably one of the main reasons for turning it into a Roman colony: its strategic position in terms of interregional trade rather than its military significance. Augustus refounded Patrai, according to Pausanias, either because it was a convevient place for boats to stop, while they were heading towards the east, or for some other reason (Pausanias, 7.18.7). Hence, the city facilitated transit movements of merchants across the eastern Mediterranean.

The coins revealed in archaeological excavations indicate a continuous flow of movements between Corinth on one side of the Corinthian Gulf and Patrai on the other, since large numbers of coins from the mint of Corinth have been found in the area. In addition, we find in the course of excavations a very large number of bronze coins minted in Rome. These probably are an indicator of the number of passing merchants coming from Italy and moving towards the East. The opposite movements may also have taken place since we recovered coins from the mints of Asia Minor throughout the second and the third centuries AD.

Comparative evidence from Asia Minor

Most of the excavations in Asia Minor present us with regional rather than interregional patterns of circulation. Specifically, the excavations in the cities of Pergamos, Aphrodisias, Ankara, Tarsus, Perge, Side, Sagalassus, Sinope revealed no coins minted in the Balkans. The coins come mostly from Asia Minor, with a few exceptions when they come from Rome or more rarely from Syria. This situation is in sharp contrast with the excavation finds we encountered in even the smaller cities of the Peloponnese. With regard to the commercially busier ports of western Asia Minor, we find similar patterns of circulation.

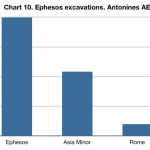

Ephesos may be the most prominent Asia Minor harbour in terms of interregional trade. Nevertheless, the 243 coin finds include only 2 coins from Greece (Philippopolis and Naxos) and 15 from Rome. The rest come from the mint of Ephesos itself and other Asia Minor cities (mostly Ionian). Specifically, in the Antonine period most coins were minted in Ephesos (50) and other Asia Minor cities (27), while only 5 came from Rome. Chart 10.

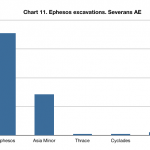

During the Severan period we notice only a slight change in the patterns of circulation. We find less coins coming from Rome, while 2 coins come from Philipopolis and Naxos. Chart 11.

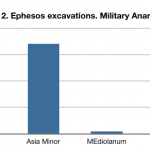

More important changes took place later in the Military Anarchy period. Unlike the province of Achaea that, by then, was importing most of its bronzes from Rome, in Ephesos seem to be circulating mostly coins minted in Asia Minor. Specifically, the coins minted in the city of Ephesos (26) were reduced and we notice the predominance of other Asia Minor mints (34). Also the mint of Rome is more strongly represented (8).

Overview of Evidence

The comparison of numismatic finds from Greece and western Asia Minor could change radically our views of the economic role of the provinces in the eastern Mediterranean. The existence of bronze coins coming from distant areas does not only confirm links to these regions but is also indicative of flourishing interregional trading centers; unlike the cities of Asia Minor that seem to have concentrated on regional commerce. Even though numismatic finds do not confirm the view that Greece was the backwater of the Roman empire, they fit well with the rest of Alcock’s findings. For example, there is a possibility that wealthy landowners drove poor peasants away from the countryside and into larger urban centers. The new urban residents could have been more actively involved in commercial activities that, in turn, brought prosperity to the region and its inhabitants. Even if the Greeks did not have enough products to exchange with merchants that came into their ports, they may have been involved in the interregional trade as middlemen. On the whole, the urban centers of Roman Greece flourished under Roman administrations and took full economic advantage of their central position within the eastern Mediterranean.

In this case, I will allow for the reader to come to their own results, before I present mine in full. As the publication is on my blog, I reserve the right to change my opinions, views, results at will!

————————————————————————————————————————–

Bibliography

Day, J. (1973) An Economic History of Athens under Roman Domination. Ayer Publishing.

Engels, D. (1990) Roman Corinth: An Alternative Model for the Classical City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fulford, M.G. (1989) ‘To East and West: The Mediterranean trade of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania in antiquity’. Libyan Studies 20: 169-191.

Hoskins Walbank, M.E. (2002) ‘What’s in a name? Corinth under the Flavians’. Zeitschrift fuer Papyrologie und Epigraphik 139: 251-264.

Migeotte, L. (2009) The Economy of the Greek Cities, from the Archaic Period to the Early Roman Empire. Berkeley/ Los Angeles/ London: University of California Press.

Shear, T.L. (1981) ‘Athens: From city-state to provincial town’ Hesperia 50.4: 356-377.

Warner Slane, K. (2003) ‘Corinth’s Roman pottery: Quantification and Meaning’ Corinth the Centenary: 1896-1996. vol. 20: 321-335.

Copyright: Dr. Constantina Katsari

Reference as: Katsari, C., ‘Imported bronze coins in Roman Achaea’, in Love of History Blog (http://loveofhistory.com ), 31st December 2014