The boldest reformers in the Roman Empire: Diocletian and Constantine

By the end of the third century AD the Roman Empire has been through 100 years of civil wars, plagues barbaric attacks and Persian invasions that run down the economy and weakened the State. Although the inhabitants of the Empire lived for years now in conditions of physical danger and economic instability, they never tried to question the decisions of the emperors and they never tried to rebel against the central authorities. The need for reforms, though, at least in the administrative section became acute both to the upper and the lower classes. The opportunity came with the rise to the throne of Diocletian, an Illyrian with Greek origins.

As soon Diocletian had the power, he attempted to change the empire he was ruling over. Until then, a single emperor was responsible for the administration of the vast area around the Mediterranean Sea. The task, though, proved to be daunting. Especially, when the barbaric tribes invaded the Northern provinces or when the Persian tried to conquer Syria. Diocletian, therefore, decided to recruit additional help, and for the first time in history he appointed a co-emperor. At Milan in 285 he adopted as his son one of his Illyrian comrades in arms, Maximian, giving him the rank of Caesar. And the next year he promoted him in Augustus, the highest imperial title. Next, Diocletian kept for himself the Greek East, while he assigned to Maximian the Latin West. Although the empire remained one political unity, in fact, there were imposed two administrative systems.

In 293 Diocletian went a step ahead and proclaimed another two Caesars, one for each Augustus. Maximian’s Caesar became Constantius, while Diocletian’s Caesar was Galerius. These Caesars were subject to the Augusti, even if they could take their own military and political decisions within the area of their jurisdiction. This system of the four emperors has since been called the Tetrarchy. In fact, it simply applied the familiar practice of putting two junior emperors to the existing diarchy.

The successful operation of the new administration allowed the emperors to relax and enjoy the fruits of their efforts. On the twentieth anniversary of Diocletian’s accession to the throne the emperor became seriously ill. Although he recovered his health, in 305 he decided to abdicate and he persuaded his co-emperor to follow the same course of action. Their joined abdication allowed Galerius to become Augustus of the East and Constantius to become Augustus of the West. Subsequently, Severan was selected Caesar for the West and Maximin Caesar of the East (both of which were friends of Galerius). Having two Augusti and two Ceasars was a source of strength for the empire, as long as they could co-operate and respect their respective obligations and privileges. However, in this case, tensions appeared almost at once. And these tensions led to the break out of a civil war.

The ultimate winner of the continuous battles was Constantine, the son of Constantius and his divorced wife Helene, an innkeeper’s daughter with a ‘reputation’ (only much later she was proclaimed a saint and equal to the apostles). Soon Constantine managed to become the ruler of Europe, while the provinces of Asia Minor and Syria remained under the governance of his co-emperor Licinius. The battle against Maxentius that gave him the right to rule over the western provinces took place near Rome in 312. It was here that he experienced his famous vision, described by Eusebius:

“…a most marvelous sign appeared to him from heaven…He said that at about midday, when the sun was beginning to decline, he saw with his own eyes the trophy of a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and bearing the inscription Conquer By This. He himself was struck with amazement and his whole army also.”

Constantine interpreted the vision as the favour of the Christian God. And reinforced by his new faith he marched against the opponents and won the battle. An ancient historian, Lactantius, provides us with another version of the same event:

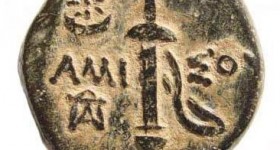

“Constantine was directed in a dream to cause the ‘heavenly sign’ to be delineated on the shields of the soldiers, and so to proceed to battle. He did as he had been commanded, and he marked on their shield the letter X combined with the letter P, thus the cipher of Christ.”

In any case, the victory not only made Constantine the absolute ruler of the entire Europe but it also marked his conversion to Christianity. In January 313 he met with Licinius in Milan and they both agreed to grant Christianity full recognition throughout the Empire.

“I, Constantine Augustus, and I, Licinius Augustus, resolved to secure respect and reverence for the Deity, grant to Christians and to all others the right freely to follow whatever form of worship they please, that whatsoever Divinity dwells in heaven may be favourable to us and to all those under our authority”.

Constantine, though, seemed to have been a Christian emperor in the wrong part of the Empire, since the Christians were more numerous in the East. When Licinius turned against the Christians of Thrace, Constantine considered it an excellent opportunity to interfere and win for himself the other half of the Roman Empire. This war ended with the victory of Constantine and the execution of Licinius (although he was promised immunity if he surrendered).

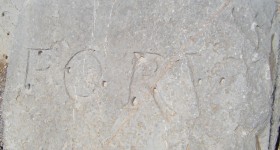

In 324 Constantine was the sole ruler of a vast empire. One of his first decisions was the foundation of a new city on the shores of Bosporus, in the place an old Greek city-state called Byzantium. The new city was named Constantinople, after the emperor’s name, and was destined to become the new capital of the empire. One of the considerations for such a decision was probably the strategic position of the city. If someone attacked from the west, then the inhabitants could have retreated in Asia Minor. If he attacked from the east, then they would have retreated to Europe. It is evident that Constantine gave particular emphasis to the security of the eastern part of the empire. Until then, the capital, Rome, was placed exactly in the centre of the Empire, since it was equidistant from the Atlantic and from Mesopotamia. The move of the capital to the East condemned in the long run the western provinces to the continuous barbaric attacks.

A second reason for the foundation of Constantinople was that the emperor needed to distance himself from the old pagan capital. The new official religion, Christianity, needed to be hosted in a new capital. Constantinople itself became the new symbol of the Christian world. And Constantine set himself the borders of the city. The story goes that one fine morning the people saw him walking, tracing out the line of the walls with his spear. When someone commented that the city is becoming too big, the emperor answered that “I shall continue until he who walks ahead of me bids me to stop”. Thus the divine foundation of Constantinople was established in the minds and the hearts of its inhabitants. The capital later was adorned with churches, palaces, a hippodrome and thousands of statues stolen from other Roman cities. In addition, his mother brought from Jerusalem the True Cross. According to tradition, she distinguished it from the ones used for the two thieves by laying it on a dying woman, who was miraculously restored to health.

The reign of Constantine, though, was a problematic one. Fierce theological debates commenced throughout the empire with regard to the nature of Christ. On one hand, Arius of Alexandria preached that Jesus Christ was not co-eternal and of the same substance as the Father. But God had created him as his instrument for the salvation of the world. Thus, the Son was subordinate to the Father. On the other hand, the opposition claimed that Christ was of one substance with the Father. The emperor became actively involved in this debate but without success. He even called for the First Ecumenic synod that took place in the city of Nicaea in 324, in which he presided. The synod temporarily solved the problem by declaring Arianism a heresy. Christ supposedly was of the same substance and equal to the Father (although this clause could be interpreted in many different ways). Nevertheless, the emperor did not keep a constant mind, despite his name. Only four years after the synod, the mother and half-sister of Constantine persuaded him to recall Arius from exile and allow him to settle in Egypt. The inhabitants of Egypt, though, as well as their archbishop would have none of it. Riots broke out in the region that soon went out of control. In the meantime, the hermit Great Saint Anthony left the Egytpian desert at the age of 86 and sided with the Orthodox faction. The upheaval was such that the emperor had no solution but to invite Arius to Constantinople for a further investigation on his beliefs. During this inquiry

“Arius , made bold by the protection of his followers, engaged in light-hearted and foolish conversation, until he was suddenly compelled by a call of nature retire; and immediately, falling headlong, he burst asunder in the midst and gave up the ghost”.

Although Constantine was involved in serious theological matters, he has not been officially baptized as a Christian. And with good reason! In the course of his life he committed enough murders that would have sent him to hell for an eternity. Among his victims were his first born son and heir, Crispus, and his second wife. The later was either stubbed or suffocated by steam in one of the public baths. That is probably one of the reasons for Constantine to be baptized only a few months before his death. When the baptism was completed, “he arrayed himself in imperial vestments white and radiant as light, and lay himself down on a couch of the purest white, refusing ever to clothe himself in purple again.” Finally, after the reign of 31 years he died in 22 May 337. His was buried in the completed church of the Hole Apostles. This way he laid claim to the title “Equal to the Apostles’ that he carries until today.

I just love history. It gives me a feeling inside. A feeling of enchantment. I wish I was born in the ancient times.

How did Commodus do as emperor? I just watched this new Netflix show called Roman Empire: Reign of Blood. He didn’t seem to do too well in that show, at least not as well as his father Marcus Aurelius did.

Here’s the trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TDHgU6ixzwk

Would love to hear your thoughts on the show. It’s one of those docu-dramas, but the reenactments are impressively done.